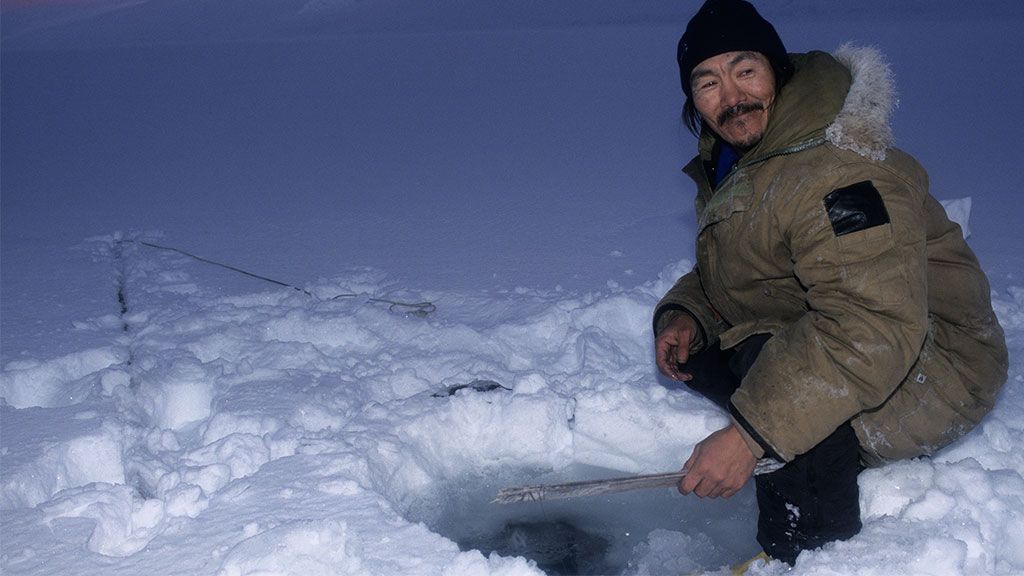

Investigating what Canadian Inuit know about sea ice

Narwhal hunters, Baffin Island

© Rémy Marion

Dr. Claudio Aporta is the principal investigator for the ISIUOP (Inuit Sea Ice Use andOccupancy Project), the Canadian component ofthe IPY Sea Ice Knowledge and Use (SIKU) project (IPY project n° 166). ISIUOP has been running for three seasons in Inuit communities in Eastern Canada and is currently wrapping up its final season and moving towards publishing the results of their research.

What does ISIUOP entail?

The main goal of the project is to document and map the way the Inuit use the sea ice - what people are doing on the ice and how they know what they know. The secondary goal was to ask what people did in the past, just to have a sense of how things have changed. In order to do this we interviewed elders, asking them how they used ice in the past, how they used it before the establishment of settlements, the use of dog sleds, etc.

To some degree ISIUOP was modelled after a famous project conducted during the 1970s called the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project, which was directed by Milton Freeman. That project was really significant because it was the first project that systematically documented the way Inuit use the land and it eventually led to the Nunavut land claims at the time.

How do members of indigenous communities participate in the project?

We basically have what we call "local researchers" - local Inuit who are working in the project monitoring the ice. In one of the communities, Clyde River, they monitor the ice with a GPS-based type of technology that was developed in collaboration with local hunters and Kyle O'Keefe, from the Department of Geomatics Engineering at the University of Calgary. This technology allows the hunters to record events, hunting spots, etc., on the sea ice. And then all this information goes into a geographic information systems database and is used to gain a better understanding of how people use the sea ice. However in the other communities we're monitoring the ice and documenting Inuit use and knowledge by mapping where and when people use sea ice, conducting interviews with hunters, and taking trips out onto the sea ice.

Has there been a decline in the use of sea ice over the past two generations in the areas where you're doing your research?

I'm not sure I would say a decline. It's important not to generalize. There are many different situations all across the Arctic and even within the Canadian Arctic. It's more about a change in how the ice is being used and the time ice freezes over and breaks up.

What the Inuit are telling us is that the sea ice is forming later and breaking up earlier, so the sea ice season is a little bit shorter than it used to be, and some areas have experienced more dramatic changes in sea ice than others simply due to changing marine currents. For example, in Igloolik, changes on the sea ice have not been as dramatic as they have been on the eastern coast of Baffin Island.

But from what we've seen, Inuit are travelling less during times when sea ice travel becomes more dangerous, like during freeze-up and break-up periods. In the past, people used to be more confident of how the ice behaved, and perhaps they were more confident of their own knowledge, too.

So climate change has had a significant influence?

Yes, to some extent. Inuit hunters also say that the ice is less reliable than it used to be. There have been more reports of people going through the sea ice.

However this is connected not only to climate change, but also to social and cultural changes. Driving a snowmobile on the sea ice is more dangerous than travelling by dog sled. You travel faster on a snowmobile, which gives you less time to react, and the dogs can sometimes sense when the ice is getting thin.

And it also has to do with education. In the past, Inuit learned firsthand by being out on the ice on a daily basis. Now people go to a school and later on get jobs, so their education has changed a lot. In general people know less about the ice than they used to.

Risk was always part of going onto the ice, particularly in a place like Igloolik, for instance, where people used to hunt on the moving ice. They would actually go out onto very dangerous pack ice connected to the land fast ice (the permanent ice); the ice could break with a change in wind or with a change in the tide. These people were experts in hunting on the ice would have had an incredible understanding of how the phases of the moon could be linked to the topography of the bottom of the sea ice and winds.

The Inuit have astounding knowledge about sea ice. Hunters could tell you where a particular block of ice or a particular field of icebergs came from, even if it came from a strait hundreds of kilometres away. They have such a deep understanding of the landscape and the environment, and this is one of the things we try to emphasize in our research project. If it hadn't been for their special knowledge and skills, they wouldn't have been able to survive in the Arctic for millennia.

Are these kinds of things taught in school in Canada?

No, they're not taught in school at all. Whatever people learn comes from elders. The educational curriculum in Nunavut doesn't really address those kinds of issues. There are always programmes, but they're isolated. Teaching and learning Inuit knowledge and skills is not systematically included in the curriculum. To some degree it's not always compatible with formal education, because the traditional way of learning is so different for the Inuit. You can't really take a concept or a theme such as Inuit knowledge of sea ice and divide it into different lessons that you teach over the course of the year. They used a more holistic approach back then. People learned mostly through firsthand experience going on the ice.

What has been responsible for this decline in knowledge?

Firstly, the Canadian government has encouraged Inuit to move to permanent settlements in the late 50s and early 60s, and their lifestyle has changed quite dramatically. Living in settlements has completely changed the setting of learning. People don't live on the land anymore to the same degree they used to. They go out from their settlements to go hunting, but not like before.

Secondly, formal education and day jobs have become more important, and the time people have to spend on the ice and land has decreased. Formal Western-style education isn't connected to Inuit knowledge; it doesn't take into account indigenous values and knowledge.

Has the amount of time Inuit spend hunting on the ice dramatically decreased?

Yes, and people have also become less attuned to environmental changes in a sense because right now people only go on the ice when they have free time: often on the weekends. They aren't as attuned to changes in the environment, the wind or the tides.

How are indigenous languages faring?

Again, you can't generalize. Inuktitut, the Inuit language spoken in Canada, is doing better in some places and worse in others. In the places we're focusing on in eastern Canada, Inuktitut is pretty strong as a language. In western Canada, however, there is more of a problem with language loss.

Why is this?

It probably has to do with more systematic contact with Westerners over a longer period of time. The Gold Rush at the beginning of the 20th century in the Yukon and Alaska might have been a factor. There's a road connecting southern Canada with northern Canada in the western part of the country. However in the eastern part of the country the Inuit communities are much more isolated, reachable only by boat or plane.

What kind of consequences has this had on sea ice knowledge and use?

In terms of what people know, things like technical terms about sea ice and the freeze-up process for instance, most people in the younger generation don't know these terms. So part of what we're doing is collecting this information before the older generations pass away. For instance we're creating dictionaries of sea ice terms, creating maps of sea ice terms and processes and mapping changes from year to year.

One of the changes people in these Northern communities have noticed is that the sled trails on the sea ice are different now. This has to do with the risks associated with travel on sea ice. The Inuit use trails in a very systematic way, both on land and on sea ice. Trails are broken on the snow every year in the same location. But in the case of the sea ice, certain trails have changed because as the Arctic has warmed, the floe edge has moved closer to the shore than it used to be, so people have to take detours to go form place to place.

How do Western and indigenous attitudes towards sea ice differ?

The approach is entirely different. To British explorers in the 19th century, for example, the sea ice was something that stood in their way. They wanted to make it through the Northwest Passage all the way to the Pacific, and the sea ice was a constant obstacle for them. If you read the journals of the British explorers, they were always complaining about the sea ice forming too early or not breaking up.

But for the Inuit, the sea ice is home. They used to have villages of snow houses on the ice. Children were born on the ice. People would live and travel on the ice. Life happened both on land and the ice for the Inuit. So in a sense, the sea ice has always been a very welcome feature.

Westerners usually don't think of sea ice as something that has a regular topography, either. But the Inuit tell us that in the same locations in certain areas, the topography of sea ice is the same year after year. They see the same cracks, the same ridges, the same leads appearing in the same locations year after year. These ice features disappear during the summer, but they return during the colder months. The Inuit would give some of these features names, similar to the way they would name other physical features such as a hill or a bay.

Has climate change altered these dynamics?

It has, although in some areas it hasn't transformed the topography of the ice. It's mostly affected when the ice freezes and melts.

What will happen to all the data you collect?

We're integrating everything into a database with the help of the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre at Carleton University. It's a geographic database that also incorporates data from various media sources including photographs on the sea ice, videos, interviews, audio clips and written material. Part of this database is going to be published and made available to the public through an online sea ice atlas we're hoping to release in 2010. However there will be a process of negotiation with each community regarding what they want to make available, so we won't publish anything that they don't want us to publish, such as sensitive information regarding where certain species of animals they depend on are located, for instance.

Claudio Aporta

Claudio Aporta is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. A native of Argentina, his resaech interests include Indigenous geographic knowledge and land use and cartographic representations of this knowledge. He is also interested in the anthropology of science and technology, and Latin American studies.