How climate change and socio-economics affect Greenland Inuit

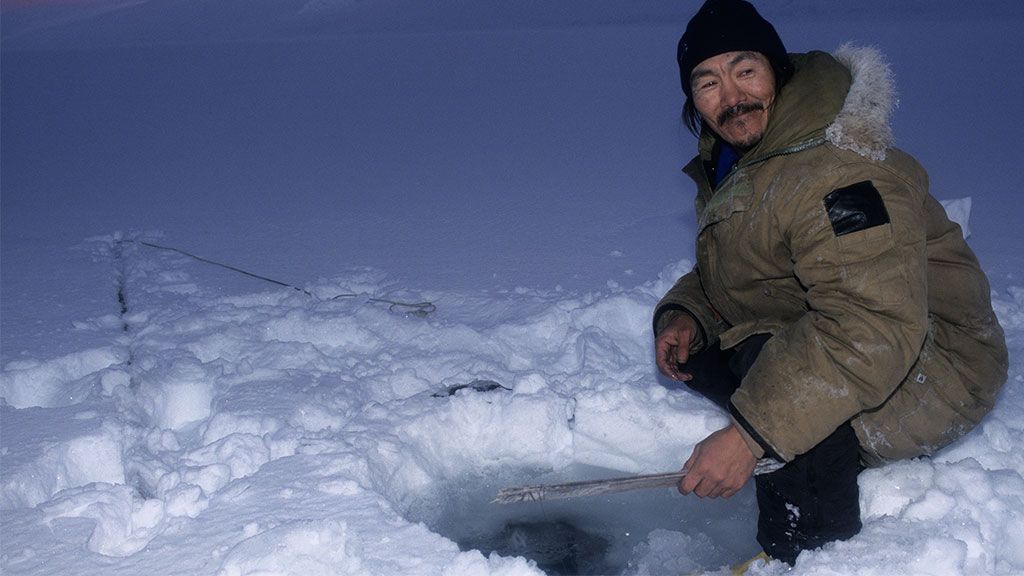

Lene Holm with Qaerngaaq Nielsen, an expert hunter from Savissivik, Greenland

© Lene Holm

Traditions, language, and knowledge about sea ice are currently strong in Inuit communities in Northwestern Greenland. However despite efforts to keep their heritage alive, Inuit living in this corner of the planet are nonetheless affected by climate change and the preservation of indigenous knowledge is being affected by external factors.

During the time Lene Kielsen Holm was Director of Environment and Sustainable Development Issues, she oversaw two research projects partnered with the Sea Ice Knowledge and Use (SIKU) project, an IPY project (n° 166) in northwestern Greenland.

In the following interview she discusses the situation of the Inuit living in this more traditional part of Greenland.

What kind of projects partnered with the SIKU project are you currently working on?

We've got two projects going on in which we work in a multidisciplinary and international setting with researchers from Greenland, Canada and Alaska together with Inuit hunters from these countries. One is called Sila-Inuk and the other is called Siku-Inuit-Hila.

The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) has its own project called Sila-Inuk. "Sila" means the weather and the human mind, and when you put "suaq" at the end, "Silarsuaq" means the universe. In Inuit cosmology these two concepts are indefinitely linked - the idea that what humans do has an effect on the world around them. Sila-Inuk has been going on since 2006, and it involves travelling to both southwestern and northwestern Greenland to interview hunters, fishermen, sheep farmers and other knowledgeable people about their observations of climate change, focusing on what they've seen during the last few years in Greenland.

The other project partnered with the SIKU project, Siku-Inuit-Hila, is designed to be quite interdisciplinary and intercultural and international. We're exchanging ways of understanding sea ice between Western researchers and Inuit hunters from Alaska, Canada and Greenland. It focuses on collecting sea ice knowledge: the hunters' personal knowledge of sea ice, how they hunt on sea ice, how they live on sea ice and any changes they've noticed. Within the project we also had some hunters take measurements of sea ice thickness last year and hopefully this will continue in the coming years.

Are you working on compiling sea ice dictionaries?

Yes. In the SIKU project we're working on sea ice dictionaries to preserve the special sea ice knowledge contained within the Inuktun (Language of Qaanaaq) dialect of the Inuit language.

How is Greenlandic Inuit faring as a language? Is it at any risk of disappearing?

The Greenlandic language, Kalaallisut, is very much alive. Young and old are speaking it, and the school system teaches in Kalaallisut.

Are there any other SIKU activities you're involved with?

We're also planning on releasing a Siku-Inuit-Hilabook in summer 2010. The book will contain drawings and photos of sea ice formations and describe various concepts regarding sea ice among other issues. We've been working with Inuit hunters from different parts of the Arctic - Qaanaaq, Greenland, Clyde River, Nunavut, and Barrow, Alaska. We hope to release it around the time the ICC holds its general assembly in Nuuk in summer 2010.

Has there been any change in how sea ice is being used in the places you're studying?

Yes. We've been seeing a lot of the changes. Sea ice has been freezing later in the winter and breaking up earlier in the spring than in years past and the thickness of the sea ice is changing. This causes the animals Inuit hunt on the ice are changing their routes, so hunters have to change their own travel routes on the sea ice, so all of these are happening. Even if the weather is as cold as it used to be, the sea ice doesn't get as thick because it seems that the water temperature is getting warmer. In some places where glaciers are receding, place names, which in Inuit languages often give a physical description of the surroundings no longer accurately describe the surroundings.

Is this happening mostly in northwestern Greenland?

Yes. We haven't been to eastern Greenland, where they also hunt with dog sleds, so I can't comment on that part of Greenland. But the northwest sure has seen a lot of changes.

Has the amount of time hunters spend on the ice changed at all in recent years?

It has, because the ice freezes later and breaks up earlier. Usually in the summer hunters track animals from small boats, so with sea ice cover changing, they're spending less time during the year hunting on the ice and more time hunting from boats. In many places the ice doesn't form by the winter solstice anymore, and during this time of year there are a lot of high winds, so if they're hunting out on the open water, it's much more dangerous.

The sun starts to go down in mid-October, and not long after that the sea ice used to start forming. However now the sea ice is much more unpredictable, making it less safe to go hunting.

Are there any factors that have impacted how the animals the Inuit hunt in NW Greenland behave?

The increase in marine traffic, change in sea ice and change in marine currents is having an impact on the routes the animals take. I'm talking about seals, polar bears and walruses. I don't think there's research out there that can conclude that their numbers are decreasing in NW Greenland, but they are changing their routes.

Has the introduction of modern technologies such as snowmobiles and GPS affected what the younger generation knows about sea ice?

North of the Arctic Circle in Greenland you're not allowed to do any hunting from snowmobiles. The ban was put in place to preserve our culture and the tradition of having dog sleds. It's different from the other parts of the Arctic.

Are there any advantages to travelling by dog sled instead of by snowmobile?

We travelled to Clyde River in Canada last year, where we had the opportunity to travel by both snowmobile and dog sled. These two ways of travelling are very different. I can tell you it's safer to go by dog sled. There was an accident last year on Baffin Island in which a whole family disappeared because their snowmobile ran out of fuel (fortunately they were later found safe and sound). You don't have to deal with that if you're travelling by dog sled. And dog sleds are also better for the environment.

Has exposure to a Western lifestyle (five-day workweek, comforts such as stores) impacted the amount of time hunters spend on the ice?

There's been an impact to some extent. But in many places jobs aren't exactly hanging on a tree. In northwest Greenland, there is much more of a subsistence culture. However the Inuit live in houses and have to pay for electricity and other utilities, so in order for earn money and make a living, many men need to be hunters. Sometimes wives also get part-time work if they can.

But recently the European Council banned the importation of all seal products. Even though they created an exception for Inuit, this ban doesn't help our people. Many hunters make extra money by selling seal skins to exporters. There's a tannery in southern Greenland where all the skins are eventually sent. There they make coats and other products and then they export them to Europe and other places. So starting on January 1st, 2010, we won't be able to export these products any longer. But now with this ban Inuit hunters won't have any place to sell their seal skins any longer. It's another threat to our hunting communities because it's taking away one of Inuit's main sources of income. It wasn't done in recognition of other ways of making a living. We'll have to see how things develop.

How does the younger generation learn about sea ice? Is this done exclusively informally or is something taught as part of the curriculum in the educational system?

No, there is no education in indigenous knowledge within the formal educational system. The younger generation learns this knowledge from their families. However they are trying to set up a school for hunters in Uummannak, so this would be the first time this kind for education will be formalised, although with the seal ban I don't know what kind of options there will be for those who want to hunt.

Have you noticed a gap in knowledge and use of sea ice between generations?

Not that I'm aware of. But of course today many of the older hunters are encouraging their children to pursue Western-style higher education before they decide whether they want to be hunters or not. We have Western-style education everywhere in Greenland, and opportunities are the same for everybody. Education is free, paid for by the self-rule government in Greenland.

Lene Kielsen Holm

Lene Kielsen Holm is a project leader in the Climate Centre's communication team and Social Science Professor at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.