Karin Lochte on the work of the Alfred Wegener Institute

Neumayer Station III

© Michael Trapp - Alfred-Wegener-Institute

Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) carries out cutting-edge research in the Arctic and Antarctic as well as in the high and mid latitude oceans. A biological oceanographer involved in climate change research, Professor Karin Lochte became Director of AWI in 2007. Earlier in her career, she was professor of Biological Oceanography at the Leibniz Institute for Marine Sciences at the Christian-Albrechts University in Kiel where she lead a research unit focused on biogeochemical cycles in the sea.

In the following interview, AWI Director Professor Karin Lochte discusses current resarch projects and the institute's priorities for the next decade.

Can you run us through the research infrastructure that AWI manages both in the Arctic and the Antarctic?

The main research infrastructure includes the research icebreaker, Polarstern, which is deployed in both Polar Regions and sometimes over-winters in the Antarctic.

In Antarctica, we run Neumayer station, on the Ekström ice shelf which is occupied all year; Kohnen station on the inland ice sheet, which is occupied intermit-tently in the summer for ice core drilling (including the EPICA climatic research programme); and we also co-manage a station, Jubany, on the Antarctic Peninsula, with Argentina and the Netherlands, where we concentrate mostly on bio-logical research to monitor the effects of changing ecosystems.

In the Arctic, we have a permanent station at Ny-Alesund on Svalbard, which is jointly operated with the French Institut Paul Emile Victor (IPEV), and is mostly dedicated to atmospheric, geo-physical, and biological research. With the Rus-sians, we co-manage a summer station in the Lena Delta, Samoylov Station, and there we mainly carry out research on permafrost.

In addition to this infrastructure, we have the Polar V aeroplane. This plane operates in both Polar regions, and is mostly dedicated to studying thickness and dy-namic of sea ice, inland ice shields, and atmospheric chemistry.

And what is the annual budget of AWI?

The institutional budget is around 100 million Euros. That covers everything from salaries, to the running of stations and the Polarstern, to research budgets.

Was any additional funding made available to AWI for the International Polar Year (IPY) 2007-2008?

Yes, the government contributed quite substantially to the IPY by investing in specific equipment. This included 36 million Euros for the rebuilding of Neumayer station, Neumayer III, and 8,1 million Euros for the purchase Polar V aircraft mentioned earlier. In addition, of course, we also dedicated AWI institutional funding to IPY research projects.

What still needs to be covered from our institutional funding is the removal of the old Neumayer II station from Antarctica.

Is Neumayer III already operational, and what are the improvements when compared to Neumayer II?

Yes, Neumayer III was inaugurated in February 2009, in time for the end of the IPY, and is already fully operational all year. All the observatories operated in Neumayer II have been transferred to Neumayer III following an overlap period for calibration, and now we have an over-wintering team of nine people currently in place and they are sending back very positive reports about the new station.

The improvements are several-fold. First of all, the new station has been de-signed and built so that it can have a longer lifespan. Whereas the older station was under the ice and had a reduced lifespan of 10 to 15 years because it was buried a little deeper every year by snow accumulation, the new station is built on stilts above the ice, and includes a mechanism to lift it up in accordance with snow accumulation, so that it's expected lifespan is somewhere in between 30 and 40 years.

The improvements are also in the observatories. Because the station is larger, it will be able to accommodate more scientists in the summer, and hopefully will also be used to increase the level of international collaboration in this region of Dronning Maud Land.

How will the energy requirements be met at Neumayer III?

First of all the station has been designed so that the energy needs are very small, and certainly no higher than for the old station under the ice. The insulation is obviously of the highest quality, and the station is divided into a series of four blocks which can be opened in summer, or shut down during the winter, when less people are occupying the station. This means that the energy demand can be very well regulated and kept as low as possible.

Energy will be supplied by diesel, but we already have one wind turbine, and this will be increased so that we can reduce our diesel usage.

Are you also thinking of using solar power in the future?

In the first instance, we will concentrate on wind power, to supplement existing systems, but solar power may also come in due course for the summer period.

Germany has taken a leading role in the project to build a new European research icebreaker, Aurora Borealis, why, and what role is it playing?

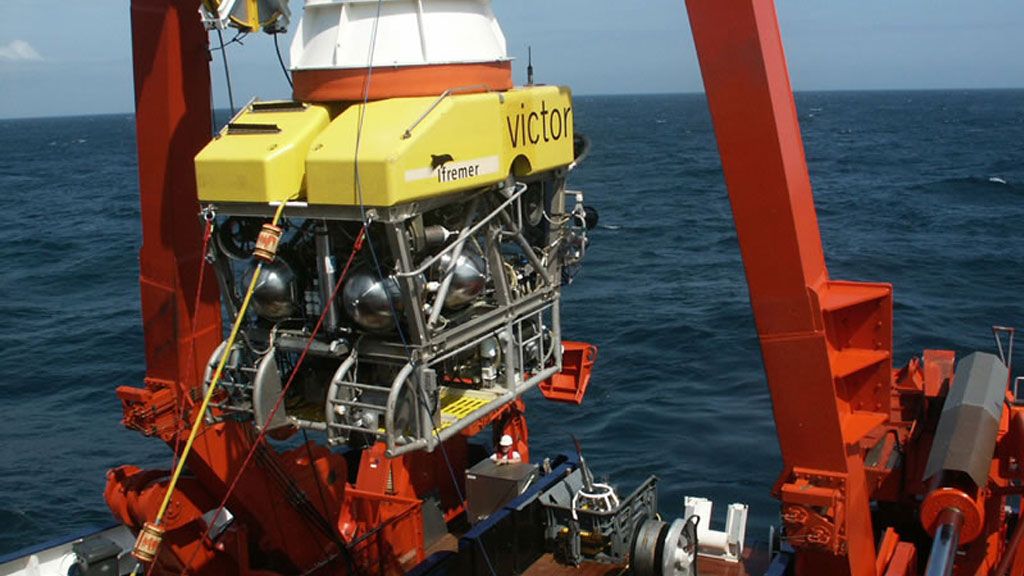

Already several years in the making, the idea behind Aurora Borealis, is to build the first ship fully able to operate autonomously, drill and explore the Arctic Ocean in both the summer and winter seasons. The drilling capacity of the ship was probably one of the major technological challenges in its conception, but the vessel will also have a second moon pool for the deployment of ROVs and other automated equipment in ice covered areas. These tools will enable scientists to research the deep Arctic Ocean, and to study a wide range of physical biogeo-chemical, biological and geological topics.

Germany has taken the lead in the project because it believes in the scientific ideas behind the project, but of course a ship of that size and capacity can only be realized with the support of the international community. Therefore, at the present time, we have a European project to try and build this consortium of sev-eral partners within Europe, but perhaps also from outside. However, negotiations are ongoing and it is still too early to say which countries will commit.

In what year will the Polarstern be decommissioned? And will Aurora Borealis be seen as a part replacement for the Polarstern, or will AWI also be seeking to build a separate replacement for Polarstern?

Unlike the Polarstern, for which Germany has 100% of the ship time, you cannot regard the Aurora Borealis as a ship for Germany, and it cannot replace Polarstern. It can only happen if it is an 'add-on', and depends on the willingness of our international partners.

So when the Polarstern, which is now 27 years old, is decommissioned in the next five to ten years, we will need another such 'work-horse' for our regular research.

What is the desired planning for Aurora Borealis?

A funding plan has to be ready by the end of next year, or the beginning of 2011, and if that is in place, we will put construction out to tender, with building and testing of the vessel expected to take two to three years. The first possible start would then be 2014-15. But I should say that that is very optimistic.

What will be AWI's main scientific objectives and priorities in the decade following the IPY, both in the Arctic and Antarctic? Which nations and/or institutes will be your key partners?

One of the main things we are doing at the moment through our station in Sval-bard is to support the Svalbard Integrated Arctic Earth Observing System (part of the Arctic Sustained Observation Network) with Norway and many other members of the consortium. As part of this, we will continue our work on the northernmost Arctic deep sea observation site in the Fram Straight, looking at, amongst other things, changes in the Arctic deep sea ecosystem and the inflow of Atlantic water and the outflow of Arctic water, both may be impacted by climate change. This is part of the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures roadmap.

We also plan to monitor the evolution of Arctic sea ice in the region North of Canada and Greenland, and of course, there is permafrost research where our main collaborator is Russia.

Another major and continued effort is data management and storage, with the Data Centre here in Bremerhaven archiving our own IPY research, but also that of our partners in order to make it accessible to the international community.

And finally, of course, we have the long-term observations that we are carrying out in the Antarctic, and which we will continue in the future.

Karin Lochte

Karin Lochte is Director of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven, Germany and a Professor of Marine Biology. Over her career, she has conducted research on the carbon and nitrogen cycles in marine environments, including investigating iron fertilisation as a potential means to sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in the ocean. Prior to becoming AWI Director, Professor Lochte has been Director of the Biological Oceanography Research Unit at the Leibniz Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Kiel, and prior to that, Director of the Biological Oceanography Research Department at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde at Rostock University.